1325 and Conflict in India: Part 2

- Padmini Ghosh, WRN India Country Coordinator

- Nov 9, 2017

- 3 min read

Part II of the our series on 1325 and Conflict in India. Read Part I here.

In North East region of India and Kashmir conflict and peace-building exercises have been quite protracted. Both of these regions have been challenged with developing an effective way to harness women’s capacities and establish a gender inclusive analysis of the conflict with gender responsive solutions.

Women's voices are regularly marginalized.

Women civil society organizations were at the forefront in the North East’s call for peace, especially the Naga Mothers Association’s “No more bloodshed” campaign. Unsurprisingly, when it came to formal peace negotiations their position was conveniently diluted. Even in early 2017, the women in Nagaland were prohibited from holding positions in local governance because of existing customary laws that prohibiting them. Examples abound of women’s voices being marginalize from decision making power structures after their organizing has achieved broader movement goals, and NGOs failing to take a gendered approach to programing.

The situation in the tribal belts of Odisha, Jharkhand, Chattisgarh depict a similar story. Women and men protested together against the effects of development politics that disadvantage their communities, yet patriarchal power inequalities saturated the campaign. For instance, in the anti-Posco movement in Odisha the male-leadership capitalized on and exploited the “undeterred commitment of women, as well as their practiced subservience to men whether as fathers, husbands or leaders”.

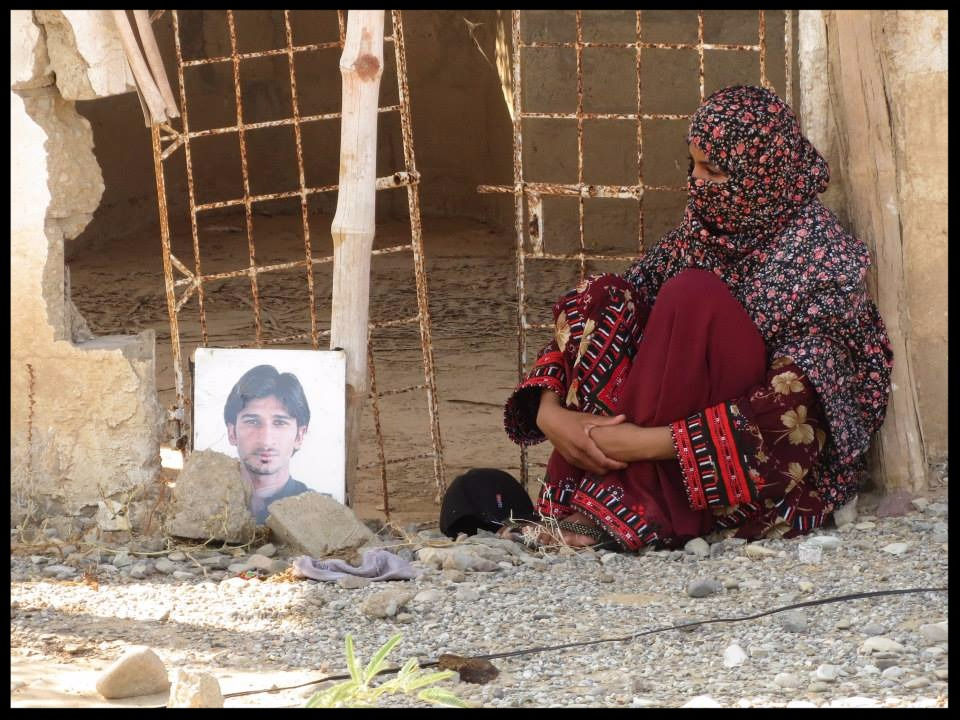

In Kashmir, the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) has become a famous NGO founded and headed by a woman. A large section of its membership are the mothers and wives of disappeared persons, known as The Half –Widows. Despite years of struggle, APDP’s prime focus is to demand the rights of the disappeared man. Although they have raised the issue of disappearance and consequent half-widows to the forefront, they do not particularly invoke the legal system to claim for the rights and security of these women who have been left behind with no job or shelter and quite a few children, as much as they do for their disappeared husbands.

Does anyone seek implementation of 1325?

Structural and cultural gender inequalities continue to hinder an effective implementation of the WPS agenda, despite a considerable number of women peace-builders working in the field. A bigger question looms large. Does anyone, apart from the women peace activists, seek effective implementation of UNSCR 1325 in India? The most pertinent issues that continue to hinder the implementation of 1325 in India are:

The Protection-Participation conundrum.

Moving beyond the sexual violence mould to include others forms of Gender Based Violence (GBV), including domestic violence, restrictions on mobility, constraints on life choices.

Lack of programing for men’s frustrations from conflict and new narratives and examples of healthy masculinities.

Lack of Preventing/Countering Violent Extremism programing for both state and non-state actors.

Lack of transformative or transitional justice mechanisms. Transformative justice in this case would entail addressing not only the episodic incidents of violent abuse of women but also underlying gender inequalities. This of course is closely related to the paradox of systemic targeting of women and use of rape and sexual abuse as a weapon of war but also treating these as collateral damage within the larger picture

Gender equality has a long way to go in India.

Women are yet to be recognized as full citizens and important stakeholders in making the decisions that affect their lives and to create alternate discourse on women, peace and security emerging from civil society. It is not insecurity that cripples alternate discourses, but rather that many women are not considered or don’t consider themselves as full citizens or developed individuals. This insecurity leads to the silencing of stories and muffling of voices, and censoring of opinions, which impede the creation of discourse from women’s perspectives.

To make UNSCR 1325 relevant to the grassroots and employ localization of 1325, we must have a mass of both women and men trained in conflict, gender and security issues. We need to move from token women representatives at the table, in conclaves and seminars, to actual deliberations on gender justice and women’s rights. The shift to bring gender-sensitive women and men to the decision making table would accelerate the vision of sustainable peace and development in India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

As with all WRN blogs written by staff, members and outside experts, views expressed are not necessarily those of all members of the networks.

Comments